Structure First – Making Talk Physically Possible

How seating, layout, and movement shape participation — with visual examples and routines for “Home” and “Active” modes.

1️⃣ Why Structure Matters

Teachers across Bangladesh often tell us they want students to “discuss more” or “explain their thinking.” Yet in most classrooms, the obstacle isn’t will — it’s architecture. Benches are fixed, aisles are narrow, and every student faces forward. Even skilled questioning can fall flat when students can’t easily look at, or talk to, one another.

If we want classrooms filled with reasoning, explanation, and collaborative thinking, the physical layout has to make that talk possible.

Talk follows direction — if every chair faces forward, so will the thinking.

Real-World Example

In a Class 7 English lesson in Khulna, the teacher asks, “What’s the difference between a fact and an opinion?” Three confident students at the front answer. The rest stay silent. So she says, “Turn slightly to the pair behind you and explain what you think.” Within seconds, the room changes: quiet voices, movement, curiosity. Nothing in the curriculum changed — only the structure.

This simple shift shows a bigger truth confirmed by research: classroom layout shapes what kind of learning talk is possible.

Core Evidence on Layout → Activity Patterns

Research repeatedly finds that the way a room is organised predicts what kind of activity — and talk — can occur. Different layouts encourage different behaviours.

| Study / Source | What It Found | Implication for Classroom Talk |

|---|---|---|

| Wannarka & Ruhl (2008) | Rows improve focus; clusters increase peer interaction. | Match layout to intended activity — rows for input, clusters for dialogue. |

| Rosenfield, Lambert & Black (1985) | Clusters/circles produced more student interaction than rows. | Face-to-face seating supports reasoning and collaboration. |

| HEAD “Clever Classrooms” (Barrett et al., 2015) | Layout flexibility explained up to 16 % of learning progress. | Even small physical changes can boost participation. |

| OECD (2017) – Innovative Learning Environments | Pedagogy, space, and routine must align. | Design classrooms that switch easily between modes. |

| Fisher, Godwin & Seltman (2014) | Over-decorated rooms reduce attention and recall. | Keep visual calm in talk zones. |

| NASEN Journal (2022–2023) | Predictable spatial cues aid inclusion and confidence. | Consistent Home↔Active routines build psychological safety. |

Layout isn’t decoration — it’s pedagogy. The direction students face determines the direction of their thinking and talk.

2️⃣ No Single Layout Is Best

If layout matters so much, the next question is obvious: Which layout is best? The answer — none of them, all the time. Rows, pairs, and clusters each serve a purpose. Good teaching is not about choosing one layout and sticking with it; it’s about moving between layouts deliberately.

| Layout | What It Enables | Typical Uses | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rows | Clear sightlines, teacher control, minimal distraction. | Explanations, guided practice, written work, exams. | Wannarka & Ruhl (2008); NASEN (2023). |

| Pairs (“turn to your partner”) | Rapid rehearsal and accountability. | Think–Pair–Share, one-minute reasoning bursts. | Wannarka & Ruhl (2008); Rosenfield et al. (1985). |

| Clusters / Circles (“turn-around rows”) | Eye contact, collaboration, shared reasoning. | Group problem-solving, peer feedback, debates. | Rosenfield et al. (1985); NASEN (2022); OECD (2017). |

These patterns suggest that teachers can think not in terms of fixed seating, but in modes of use — purposeful configurations that match the learning goal. That brings us to one possible model teachers can adapt to their own rooms.

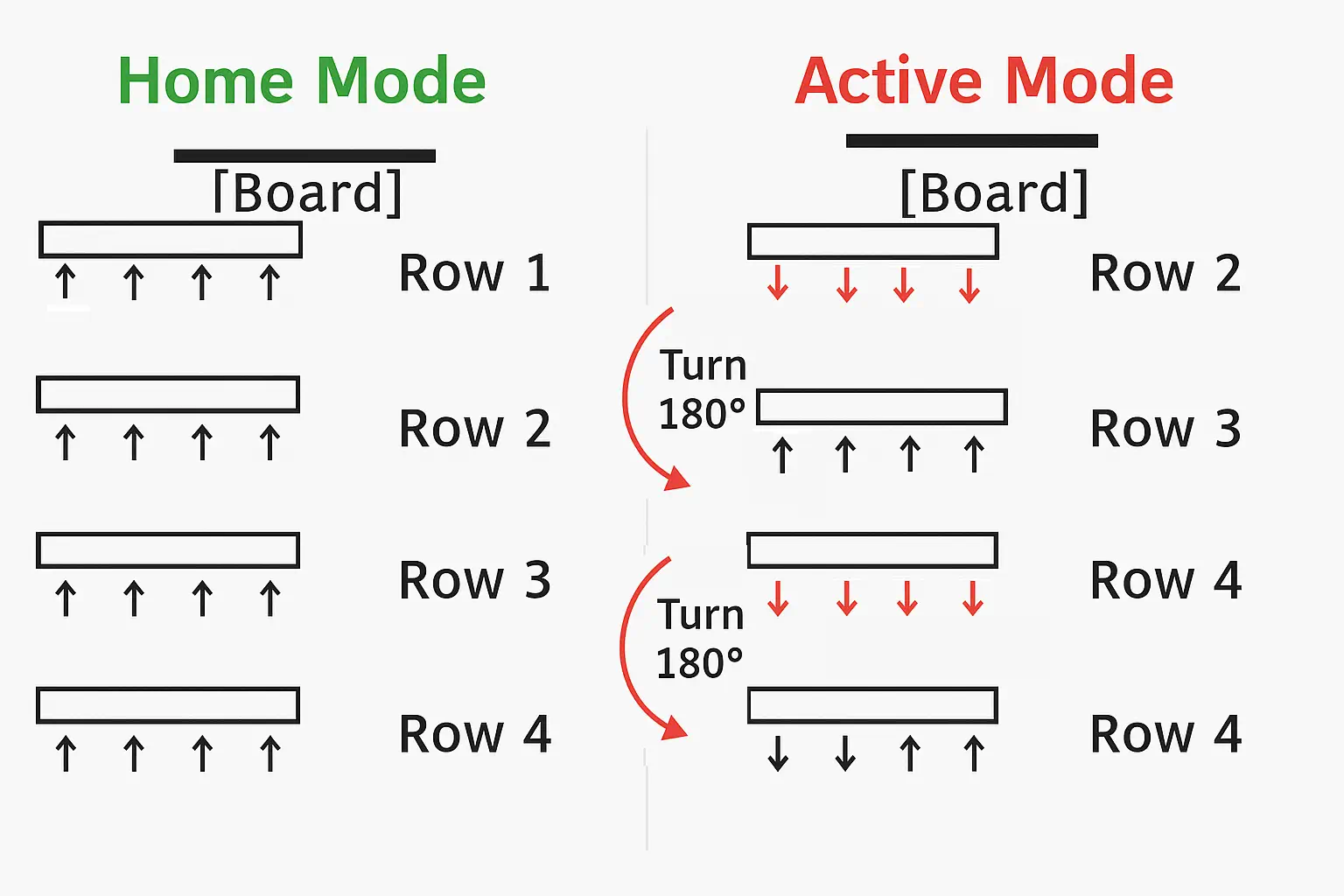

3️⃣ A Possible Solution — The Two Modes: Home and Active

This model is not a rulebook; it’s a thinking tool. It helps teachers balance control and collaboration by creating two predictable “modes” of classroom space.

| Mode | Purpose | Physical Layout | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home Mode | Whole-class teaching, clarity, and control. | Students face the board in rows or pairs. | Lesson openings, explanations, guided practice, summaries. |

| Active Mode | Collaboration and reasoning. | Students form clusters or circles (turn-around rows). | Group tasks, peer feedback, debates, reflection. |

Running Example Continued

Back in Khulna, the teacher formalises what worked: “When I say Active Mode, odd-numbered rows turn 180° to face the even rows behind them. Even rows stay where they are.” They practise twice. It takes 15 seconds. Now the class can shift seamlessly between explanation and discussion — no chaos, no lost time. Structure has become part of the pedagogy.

4️⃣ The Movement Routine + EBTD Seating & Talk Framework

Changing layout can feel risky in large classes, but predictable cues keep movement safe and efficient.

“Everyone, switch to Active Mode — odd-number rows turn 180°, even rows stay. You have two minutes to discuss.”

“Return to Home Mode — eyes front.”

| Mode | Layout Configuration | Talk Pattern & Activity Type | Purpose in Lesson | Evidence Base |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home Mode | Rows / Pairs | Controlled teacher-to-student talk with short paired rehearsal. | Explanation, modelling, guided practice, checks for understanding. | Wannarka & Ruhl (2008); Rosenfield et al. (1985); NASEN (2023). |

| Active Mode | Clusters / Circles (turn-around rows) | Student-to-student reasoning, peer feedback, collaborative dialogue. | Problem-solving, debates, reflection. | Rosenfield et al. (1985); NASEN (2022); OECD ILE (2017). |

Terminology & Routines

- Home Mode = Rows + Pairs – “Turn to your partner.” Brief reasoning or answer rehearsal. “Return Home.” refocus attention.

- Active Mode = Clusters / Circles – “Switch to Active Mode.” Group reasoning with roles (speaker, recorder, reporter). “Return Home.” reset quickly.

Predictability = Safety. When movement feels safe, thinking feels possible.

5️⃣ Implementation Strategies — Analysing Your Room

Every classroom has limits — but all have potential. The aim isn’t redesign; it’s re-imagining how existing space works.

Step 1 – Sketch your room

Identify where students can see and face each other, and where sightlines block interaction.

Step 2 – Find quick wins

• Can one row turn to another?

• Can two pairs form a mini-cluster?

• Could a side aisle serve as a temporary “Active Zone”?

Step 3 – Practise the cues

Rehearse “Switch” and “Return Home” until transitions take under 20 seconds. Praise the smooth changeover before focusing on the talk itself.

Prompt Questions for Action

- When do I need control (Home) vs dialogue (Active)?

- What one physical change could make peer talk easier tomorrow?

- How can I signal mode changes clearly so students feel secure?

- How will I know if structure is improving engagement?

Mini-Reflection — Back to Khulna

After a week of practice, that same teacher reports: quieter students are finally speaking. Not because confidence appeared overnight, but because the structure created the opportunity. Space became the silent partner in learning.

6️⃣ Conclusion

Structure shapes behaviour. If we want students to reason, challenge, and collaborate, the room itself must make that behaviour physically possible. By building simple, repeatable transitions between Home (for focus) and Active (for reasoning), teachers turn classroom space into a living part of instruction.

Next Page → Modelling Talk – Teaching Students How to Learn Through Dialogue

If you found this useful, join the EBTD newsletter for monthly, research-backed tips, free classroom tools, and updates on our training in Bangladesh (BD) — no spam, just what helps. Sign up and share this blog with colleagues so more teachers can benefit. Together we can improve outcomes and change lives.